Asynchronous and synchronous motor

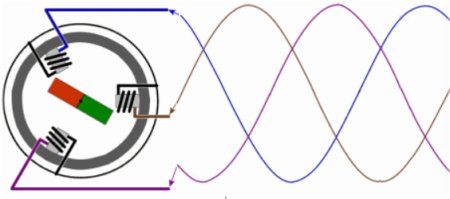

| By the way, the cable colors match the wiring shown below. |

You hear a lot about this topic, which is also so important for electric cars. Here is an attempt to compare the two and highlight the differences.

First of all, we are dealing with three-phase machines here. They are both brushless, which means that there is no direct electrical connection of any kind between the outside world and the rotor, the rotating part. But that

does not mean that power lines cannot be laid in it.

This is particularly the case in the stator, which is always a fixed part of a three-phase machine. Stator does not necessarily mean that it surrounds the rotor, but there are also designs in which the rotor rotates around the

stator (last video below). However, since we are looking for information about electric motors in electric cars, we are excluding this design here.

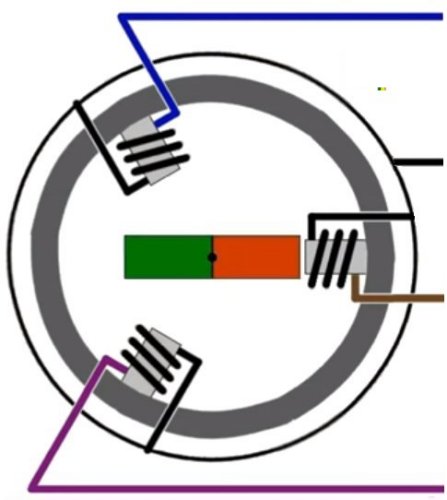

Three-phase current, in the picture on the right, are the three phases in which the voltage never matches at a certain point in time. Basically, there are three alternating currents, in the picture on the left, which are in a certain

relationship to each other. To simplify things, you can imagine that they were generated in a generator where a magnetized rotor induced voltages in three windings offset by 120° from each other.

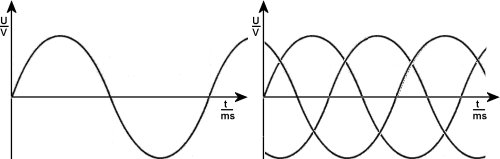

The same thing, only in reverse, now happens in a synchronous motor. It is important to mention that the rotor can consist of a neodymium magnet (rare earth), which develops significantly more magnetic force relative to its

mass than a conventional ferrite magnet, important for saving weight on the electric car's motor.

The rotor of the asynchronous motor is not magnetic by itself, so this is really an important difference. It is criss-crossed by current conductors in which the magnetic field generated by the stator produces electromagnetic

force, which is initially lower than that of the synchronous motor, which can therefore generate more torque when starting up.

| Stator of a conventional three-phase generator . . .

|

Regardless of whether it is generated electrically or purely magnetically, north poles in the rotor are initially opposite south poles in the stator, which of course also applies to the south poles in the rotor opposite the north

poles in the rotor. In order for something to happen, the poles in the stator must switch to their respective neighbors in the required direction of rotation.

The wiring of the stator in a three-phase motor differs from that shown above in case of a generator. Here, the individual electromagnets are switched individually, in such a way that an electromagnet with the north pole

towards the rotor always follows one with the south pole towards the rotor and vice versa.

| By changing the circuit, a three-phase motor can work like a three-phase generator. |

In both motors, the fields have to be controlled alternately in the direction of rotation using sophisticated electronics, so that the rotor runs behind the fields like a dog. The speed of the change determines the speed of the

rotor, which is always adjusted in the synchronous motor.

We could actually end our description at this point if there weren't significant differences in the behavior of the two types of motor. In a synchronous motor, the magnetic field in the rotor is very strong and rigid. It will therefore

switch to the next electromagnet in the stator with great force. In principle, it has no other option than to always follow the switchover exactly.

| Synchronous motor: Rotor rotation speed = rotation speed of the rotating electromagnetic field |

The opposite becomes a problem. The more load it is subjected to, the more it will eventually lag behind. But since it is called a synchronous motor, the angle of lag is not arbitrary. You can say that, for example, its north

poles in the rotor may only move so far away from the south poles in the stator until they are in the middle, halfway to the previous north pole.

If the distance becomes a little larger, the power of the synchronous motor is gone. It is then no longer synchronous. There may be circuits that help solve the problem, but they are not the topic here. If the rotor of the

synchronous motor lags behind by more than half the distance between the electric magnets in the stator, then it stops and only hums audibly.

As you can already guess, the asynchronous motor is significantly different here. Hence its name. Its magnetic field is generated from the outside, so to speak. So a kind of reorientation occurs when there is a delay. This

affects the electromagnetism in the rotor. It then runs even further behind the rotating magnetic field, it is no longer synchronous, i.e. asynchronous.

The asynchronous motor is much less sensitive to overload than the synchronous motor, which in principle cannot be overloaded indefinitely. Of course, overloading the asynchronous motor is always associated with

greater heating. In the next chapter, a further development of the rotating field machine, the reluctance motor.

|