Specific consumption Specific consumption

The average pressure is therefore determined across all strokes. It can be increased by applying more pressure, e.g. through better filling. However, one of the pressures to be reduced can also be lowered,

e.g., by means of a finer exhaust gas routing, which ensures less exhaust gas back pressure. If you manage to achieve roughly the same or even better pressure conditions with a smaller displacement

(downsizing), this will also increase the medium pressure.

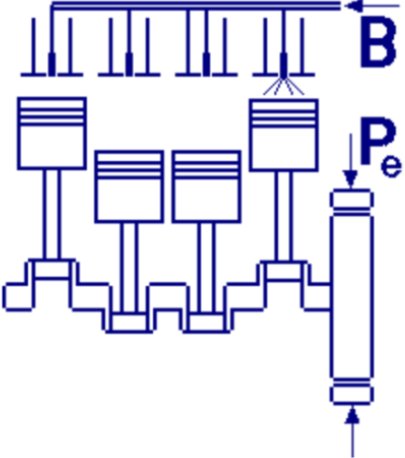

As you might expect, this pressure is directly related to the performance of the combustion engine, or more precisely, its internal or indicated power:

Have you noticed that it's not quite the same equation we had before? The ‘p’ has become a ‘pi’ (actually ‘pmi’ for ‘medium’). The internal performance therefore depends on the medium pressure, the displacement, and

the speed. To improve performance, at least one of these parameters is always increased.

This last sentence is certainly true for the indexed performance, but not for the effective performance. A very simple example: if you manage to make the pistons glide more easily over the cylinder tracks by coating them, you

will also achieve a slight increase in performance. But where does this appear in the calculations?

To do this, we must strive for efficiency. It compares the indexed performance with the actual performance, so to speak. It could also be used as a benchmark for the efficiency of the motor being driven. This is because

the difference between the two values is what is lost from the theoretically possible performance due to losses during its realization.

Now one might get the idea to subtract the power dissipated from the performance supplied. Then two motors, one with 1000 kW and another, would have the same efficiency if they both lost 50 kW each. That can't be right,

because it doesn't give enough credit to the much better former engine. In addition, the degree of efficiency would then have the unit 'kW'.

The degree of efficiency is rather calculated by dividing the lower output power by the higher input power. It is therefore always less than 1 and dimensionless. You can even multiply the amount calculated in this way by 100

to obtain the percentage, in this case the power remaining at the output. Degrees of efficiency occur everywhere along the path from the engine to the drive wheel.

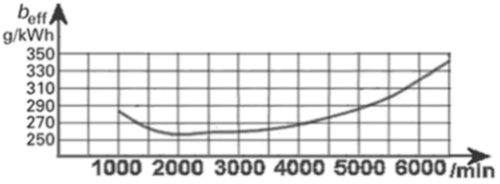

One can assume the energy stored in the fuel. But I warn you, this is also somewhat disappointing with our current engines. Let's take the test bench diesel engine from the previous chapter, which was already quite

economical with a consumption of 220 g/kWh at 100 kW continuous power. It then consumed 200 g/kWh times 100 kW = 22,000 g = 22 kg of fuel per hour.

The energy stored in fuel is expressed in terms of its calorific value, which is 42,800 kJ/kg for diesel fuel. Multiplying this by the 22 kg consumed per hour gives a total of 941,600 kJ. Now you just need to know

the conversion from kJ to watts:

So we divide 941,600 kJ by 3.6 and get 261 kW. That's how much power was contained in the fuel consumed in one hour. 261 kW went in, 100 kW came out, resulting in an efficiency of 0.383 (approx. 38 percent). All that

beautiful energy lost through heat for cooling and exhaust gases, as well as through movement for exhaust gases. Ultimately, all losses are converted into heat.

|