Indexed performance Indexed performance

Are we any cleverer now? We identified the pressure on the piston as the decisive factor and, in the case of the suction engine, the displacement. But pressure can also be applied from outside, e.g. by charging. Yes, even

a high compression ratio can help generate torque to a certain extent. As you can see, the old formula that displacement can only be replaced by more displacement no longer applies without restriction.

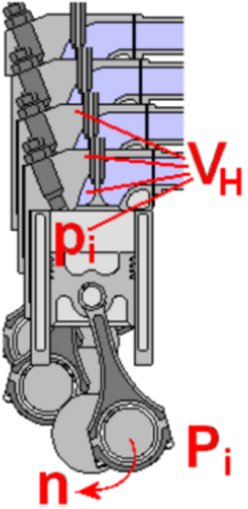

Which brings us to performance. Later, it will be explained that this refers to the internal (indexed) performance:

Here you can see in formula language what we have already worked out mentally. Whereby the engine speed has been added here for the performance. This clearly shows how different the characteristics of performance

are compared to torque. The latter is the sheer rotational force, while the former continues to increase even when the torque remains constant or even decreases slightly as the engine speed increases.

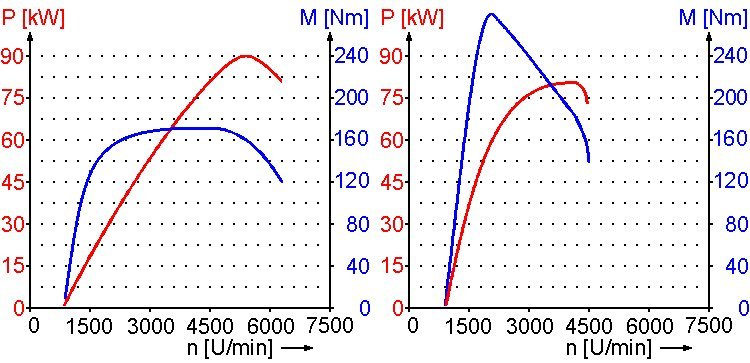

Here you can see the relationship between torque and rotational speed for the gasoline engine on the left and the diesel engine on the right. It should be noted that a curve for torque is fixed at the moment when the one for

performance is fixed, and vice versa. In other words, both depend on each other. So if I know the torque of an engine at a certain rotational speed, then I also know its performance at that point.

On the right, you can see proof of the claim that performance can increase even though torque decreases. This applies to the range between 2000 rpm and 4000 rpm. This results in the high-speed concept. Attempts are

made to maintain the fuel mixture reasonably well despite the limited time by various modifications to the engine control system, resulting in a performance output that continues to increase with engine speed. However,

the left motor stops at 5500 rpm and the right motor at 4200 rpm.

Take your time to examine the different characteristics of the two naturally aspirated engines, which have roughly the same displacement. On the right, the early rise in torque potential, and on the left, the gasoline engine,

which only really comes to life at a certain speed and revs nicely to the top. Obviously, for example, the left engine is much better suited for a motorcycle than the right one.

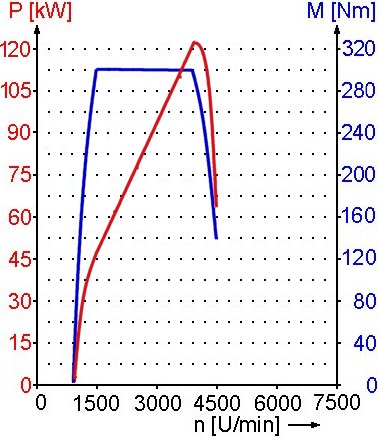

Here we have a diagram of a diesel engine with (turbo) supercharging. Typically, you would find in the data:

Maximum torque: 300 Nm at 1500-4200 rpm |

That is the effect of boost pressure control. The charger is designed so that it could generate much more boost pressure, and the peak that would seriously endanger the engine is avoided by limiting the boost pressure.

This results in a characteristic that generates sufficient torque even at relatively low engine speeds. The gear indicator takes care of the rest by demanding downshifting below approximately 1500 rpm.

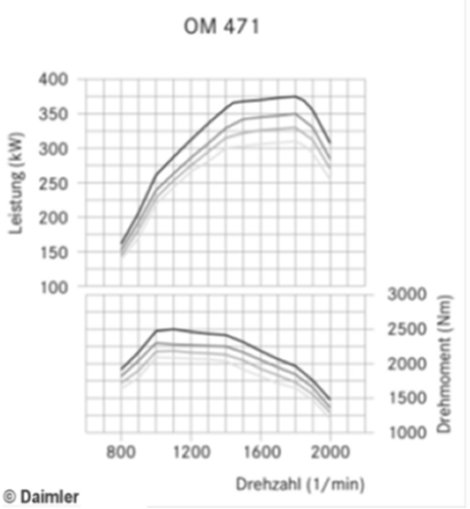

Here you have a diagram from the truck manufacturer showing even finer adjustments to the boost pressure for three different engines. In other words, the three are not that different after all. This is because manufacturers

of diesel engines, including those for passenger cars, are increasingly moving toward offering only one displacement and then designing it in different ways. This one here has 6 cylinders and 12.8 liters.

Before we get to the all-important topic of fuel consumption, let's briefly discuss power-to-weight ratio, which is not insignificant in this context. This also opens up the possibility for misunderstandings, depending on

whether it refers to the engine or the entire vehicle. There are huge differences even within the two groups.

For example, if the oft-cited Formula 1 had a vehicle power-to-weight ratio of 1 kg/kW, this is likely to have deteriorated in the 2014 season due to increased weight and reduced power. A heavy-duty truck without load,

including a semi-trailer, on the other hand, consumes 40 kg/kW, although this value is not easy to determine given the wide variety of equipment available.

If you only consider the engine, the range becomes considerably smaller. Here, 0.15–2 kg/kW are realistic values, which speaks highly in favor of large engines. These are important indicators of the quality of engineering

work. However, an overly radical reduction in power-to-weight ratio always raises suspicions about a lack of durability. In general, however, the durability of engines has increased significantly, especially in the truck sector.

Let's move on to a value that used to be emphasized so much: power per liter. As long as the changes only affected the valve train and fuel injection, it might still have been interesting, but who wants to compare engines in

terms of kW per liter of displacement since they became supercharged? And in diesel engines, it is almost exclusively installed in this form now.

|