|

|

|

Driving school 2 Driving school 2

Yes, we dare to give even the most experienced drivers among you tips on driving. We'll come back to the diagram above later. First, let's talk about how to behave when overtaking. Do you know why I actually like tailgaters

behind me on the highway? Quite simply, I'm relatively sure that I'll be rid of them soon.

So to the right, as soon as it is possible while maintaining my approximate speed. I find it much more unpleasant when people are at exactly that angle diagonally to my left for minutes or even longer so that it is not

possible to pull out safely to overtake. I also find people who are obviously too distracted while driving suspicious.

I have taken the following example from Ernst Fiala's biography. He was surprised by the behavior of some of his fellow travelers on the country road. Someone closes in from behind and you suspect he/she want to

overtake. The mere fact that he is approaching proves that he wants to travel faster than you do. So why not make it easier for him to overtake, instead of endangering both, for example, by even slightly accelerating?

An old rule says, "You should drive uphill in the same gear as downhill." Actually, it just wants to point out that you should use the engine brake when going downhill, i.e., select the gear that requires you to use the brakes

as little as possible. However, if the engine gets too close to its maximum speed, you will need to help it along a little with the brake.

There are people who you keep overtaking on the highway, even though you're driving with cruise control. There is little one can do to change these circumstances without perhaps driving much slower. But perhaps at

some point they should also realize how relatively costly and rather pointless overtaking maneuvers are, and either drive more evenly or stay behind this car, because so far it hasn't made any sense.

As I said, I like people who know what they want, as long as they don't express it by tailgating or flashing their headlights. They should drive, while I often only drive a little faster until I find a so-called 'island of bliss'. When

there isn't too much traffic, these are areas with larger gaps. I then stay there as long as possible until the situation changes again.

I also detest people braking very often without sense. They should be reprimanded for every brake application, even the slightest. If braking was necessary, they will consider it no big thing; otherwise, they should find it

downright unpleasant. For example, at the very beginning of a construction site. It was announced a long time ago, so you know what to expect. You could get used to it early enough.

| Every acceleration costs extra. |

But that's not all. Some step on the gas again so that they can brake really hard at the next exit. They should know this exit very well. After all, their behavior does not usually affect traffic behind them. Presumably, above a

certain traffic volume, almost every small braking maneuver will develop into a full-blown traffic jam, which of course the person braking will not experience.

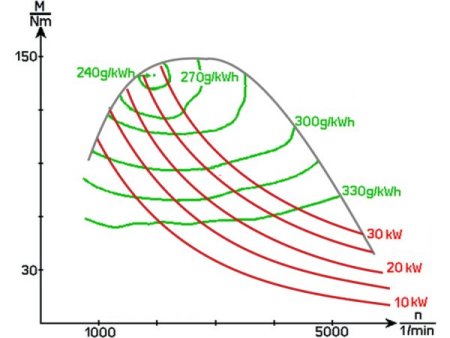

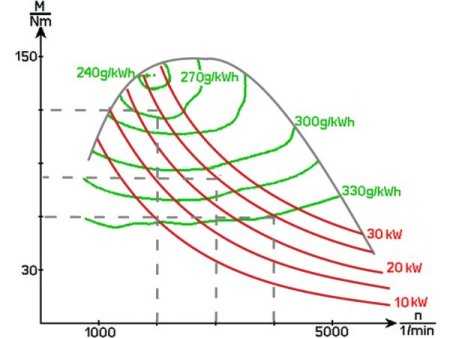

The familiar diagram can also be used in driving schools. The torque is shown in the y-direction at the top. The performance curves have been added. You can verify that these values are approximately correct,

for example, by calculating the point 120 Nm on the y-axis and approximately 1200 rpm on the x-axis using the formula P=M*n/9550. It should come out to 15 kW. Or you take 30 Nm at 6000 rpm and arrive at 18 kW, which is

about right.

And now there is another important point to consider, namely the accelerator pedal position, which must of course be at maximum if you want to drive along the torque curve. Anything below this torque curve cannot be full

throttle. For simplicity's sake, let's assume three different gears, e.g., if 25 kW is required, then 4000 rpm in third gear, 3000 rpm in fourth gear, and 2000 rpm in fifth gear, to make it easier to calculate and draw.

| Accelerating hard is good for saving fuel in this case . . . |

On the left, you can see approximately how much you need to accelerate. Only 40 percent torque is required in third gear because it pulls much better. In the fourth, it rises to over 50 percent, and in the fifth, to 80 percent.

However, the shell curves are important. There, you end up with around 330 g/kWh in third gear, 305 in fourth, and 270 in fifth. Assuming a difference of 30 g/kWh between the individual gears, this amounts to 750 g/h at 25

kW, or approximately 1 kg at 80 km/h.

That is more than one liter per 100 km, a value that is repeatedly demonstrated in practice. For gear jumps in the lower gears, the result is slightly higher, and for the higher gears, slightly lower. It follows that you should

use the highest possible gear, even when going uphill, for example. If the engine can still manage that in fifth gear, then please, go ahead, even at full throttle and just above idle speed. For safety reasons, keep an eye on

the coolant temperature. This could force you to shift down a gear.

The counterargument would be that the lowest point of the shell diagram is at 2,000 rpm and not at 1,000 rpm. That's right, but to do that you would have to find a mountain route that demands the maximum torque possible

from the engine in fifth gear. But how fast are you going at 2000 rpm in fifth gear? Can the mountain route even handle that? The minimum of the shell curve is therefore more of theoretical significance.

Now think about it! Which engine is more likely to achieve this point, a large one or a small one? Who is more likely to reach the limits of their torque reserves? The little one, of course. Because

it is full throttle (or rather full load) and remaining in this operating state is the condition. Here we have one of the reasons why a smaller engine can be more economical than a large one.

|

|