Pressure generates force 3 Pressure generates force 3

Now we have at least talked about first-order mass balance. Put simply, it affects all forces that occur at the frequency of a crankshaft revolution. You could therefore recognize their balance by the fact that the corresponding

shaft has the same speed as the crankshaft. You can see from this that this type of compensation is rare in vehicle engines.

Here, balance shafts, if present, usually rotate at twice the crankshaft speed. So you are trying to balance second-order mass forces. There are rather fewer engines in which the first-order inertial forces are not balanced.

In addition to inline and in-line two-cylinder four-stroke engines and odd numbers of cylinders in a row, all V engines and their derivatives must also be mentioned here.

By the way, there is nothing that cannot be explained in a little more detail. At first glance, the two-cylinder two-stroke engine has balanced inertial forces of the first order due to its counter-rotating pistons. However, since

one cylinder is located at the front and the other at the rear, a tilting moment occurs around the transverse axis toward the front when the front piston moves toward BDC and the rear piston moves toward TDC.

Conversely, the same applies. This only ceases to occur with an even number of cylinders when there are four or more cylinders in a row. This is typical for so-called free moments, which of course also exist in first and

second order, depending on whether they occur simply or twice with each crankshaft revolution.

Second-order mass forces, on the other hand, arise from the lateral forces that can occur in the crank mechanism, e.g., at 90°. The gas forces acting on the piston initially generate a force directed straight towards the

center of the crankshaft, but this force must be divided between the connecting rod force and the side force. These forces are balanced when there is another cylinder with a connecting rod position of exactly 270°.

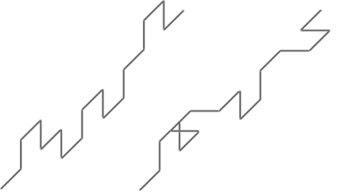

The four-cylinder in-line engine provides a good example of this. As it occurs worldwide, all its cranks lie in one plane (in the image above left). However, it would also be possible to have a form in which each crank had its

own layer (see image above right). Each connecting rod position would be countered by another position offset by 90°. This would balance the second-order mass forces, but not the first-order forces.

Why didn't the right crankshaft make it into series production? Because there are also ignitions with corresponding gas pressure. And these could not be displayed evenly over 720° here. For example, if you start with the

first cylinder at the bottom, you can run the third cylinder 180° later, but then you will have none left that is at TDC after another 180°.

It's difficult to reconcile all ideals. Incidentally, with certain multi-cylinder designs, it is even more common to have to compromise when distributing the working strokes. And the mass moments of at least the first order

would also occur in this unusual form of crankshaft, in contrast to the normal form.

| 1 = Main bearing, 2 = Connecting rod bearing |

kfz-tech.de/YVe15

|