|

|

|

Britannia Britannia

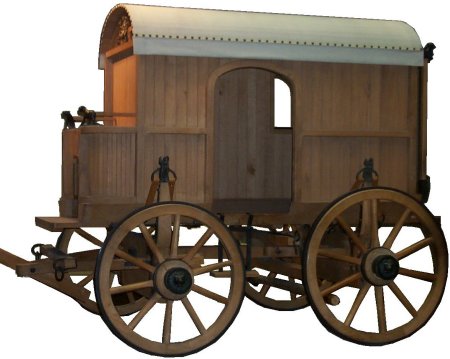

Roman chariot, Roman-Germanic Museum, Cologne

Why did Great Britain have such a difficult time with Brexit? The question is actually quite easy to answer, perhaps even including the reason for leaving the EU. Rome is always cited as the

first world empire, but the one

with the largest geographical extent was (Great) Britain. And that's exactly where we want to start, because although the Romans built an incredible number of roads across Europe, they

traveled them, at best, with

carriages (pictured above).

For core Europe, with the exception of the Vikings, mobility away from the coasts actually began with the spectacular sailing voyages of the Spanish and Portuguese around 1500.

Subsequently, it was not so much about

the transport of people, but rather of goods, riches from Central and South America, primarily to Spain. And the only Portuguese-speaking country at that time was Brazil.

The extent of the wealth there was demonstrated by the raid on a Spanish treasure caravan in Panama by Sir Francis Drake and his soldiers, in which, among other things, half a ton of gold

was captured. In this way, the

British became beneficiaries of Spanish conquests, effectively acting on behalf of the state. After all, Drake is still on everyone's lips today (picture).

Drake's ship, exhibited in London.

This was the era of Elizabeth I (1533-1603), her reign lasting 45 years, during which she achieved worldwide fame, not least thanks to William Shakespeare, due to her conflict with Mary

Stuart. We continue to discuss the

struggle with Spain, for example, through further preemptive attacks by Drake, even directly against the Spanish fleet. The decisive battle against Napoleon, however, was the Battle of

Trafalgar in 1805, in which Admiral

Nelson died, although his fleet was victorious.

Monument to Admiral Nelson, Trafalgar Square London

It is said that after this, there were no significant obstacles left to England's rise to power. During the 63 years of Queen Victoria's reign, beginning in 1837, its sphere of influence expanded to

encompass approximately one-fifth of the world's land area, stretching from western Canada to Australia and New Zealand, and south to Cape Town. Within these borders, not only the African

continent, but also, for example, the Indian continent. It is said that this country of 250 million inhabitants was governed by only 1,000 officials and 70,000 soldiers.

Ironically, Mahatma Gandhi, who had studied in England, contributed to India's independence in 1947 through his non-violent resistance. Much earlier, British, Irish, and Scottish immigrants to

America, many of whom had sought religious freedom too, had successfully rebelled against the mother country. Despite this, trade continued between the two, accounting for one-third of

British foreign trade.

What does this have to do with mobility? All these activities, mostly related to colonialism, brought immense wealth to England. This wealth was then invested, for example, in inventions. The

resulting Industrial Revolution had a tremendous impact on people's mobility; for example, within just a few decades, the majority of the population shifted from rural to urban areas.

The steam engine was undoubtedly the trigger for the centralization of work. While steam-powered land vehicles had existed earlier, the invention of the railway was of far greater significance.

For thousands of years, people had moved on land at no more than the speed achievable by horses; now, for the first time, a significant increase in speed became possible.

Photo taken at the London Transport Museum

In 1825, at least one locomotive transported people for the first time, although the rather expensive development of the railway network across the country was undoubtedly driven and

financed by the economy. It's incredible how many areas of life were ultimately affected by this. Goods stayed fresh and newspapers remained current thanks to faster transportation. And what

made all of this possible? Coal, which at that time was also referred to as England's gold.

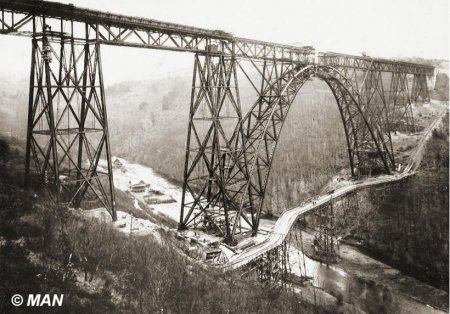

All other countries could only follow suit, including countries like the USA and Germany. Here, the production of locomotives was only slowly getting underway, as the difference in knowledge of steel production was too

great. This also affected the development of transportation infrastructure. For the first time, the costs for building a bridge were broken down into actual construction costs and the significant preparatory work required for the

production of prefabricated metal components.

1897 Müngstener Brücke (formerly Kaiser-Wilhem-Brücke), the highest railway bridge in Germany

Bridges, like tunnels, are necessary because the grade-climbing capacity of trains is very low, especially for freight trains. In mountainous terrain, tunneling involves blasting operations and carries a high risk of injuries and

fatalities. The costs are enormous, which explains why, despite its current status as a model railway system, Switzerland's railway network only began to develop after the mid-19th century, due to its relative poverty at that

time.

Photo taken at the London Transport Museum

These are images from the construction of the London Underground, showing both tunnel excavation (top) and open-cut construction (bottom).

Photo taken at the London Transport Museum

In the mid-19th century, London had a population of around 2.5 million and was, and still is today (with over 8 million inhabitants), the most populous city in Europe. Initially, the underground railway was simply an extension

of the railrod into the city. It is the oldest underground railway system in the world, has the longest network in Europe, and was opened in 1863, using steam locomotives (see photo below).

Photo taken at the London Transport Museum

Only later did it become the famous Tube, which takes its name from its tunnel-shaped, narrow tubes. Electrification using side-mounted current collectors was introduced in 1890.

Below you can see the changes in the rolling material over time.

Photo taken at the London Transport Museum

|

|