Wood 2 Wood 2

| Peugeot 1926, already with crank windows

|

As you can see from the picture above, wood is our theme. Sure, there may have been exceptions, namely bodies made from sheet steel and even aluminum, but up until the mid-1920s, wood was the dominant body

material. The latter was important, because underneath was a frame made of so-called 'pressed steel', which was also stipulated.

No, large sheet metal presses in today's sense only slowly became decisive for body construction afterwards. Perhaps Citroën deserves a special mention because here has been sheet metal processing since the

early 1920s. By the way, pressed steel was hardly anything else than today's rolled sheet steel and then processed in presses.

It has been possible to produce this for frames since around the turn of the penultimate century, but the quality is far from comparable to that of today. The profiles were therefore significantly higher, forming two longitudinal

beams, at least connected to one another at the front by the firmly bolted engine and otherwise by traverses. And what the frame could not do in terms of strength, the body usually provided more than enough.

It was heavy because it was particularly stable, mostly made of beech wood. In principle, relatively quick to produce, of course in individual parts by hand, but with special machines such as band saws, which could saw

around corners, so to speak. So curved contours were not so difficult to make here.

But the problems started with the surfaces. They were mostly made of ash wood and not particularly smooth. However, the cumbersome and time-consuming painting matched to this. This was done by spatula and brush

application, because compressed air for such work was only invented after this time. There was also no nitro or even synthetic resin paint. A kind of oil was applied, which each time required corresponding drying times.

So if you built bodies yourself, and that was very few manufacturers, you either had a small series or had to provide enough space for drying them. Because this took at least 24 hours, the entire process lasted for about three

weeks, also because of the many layers and the grinding and reworking that was always necessary.

Wood is a material that 'lives', and that is rather not compatible with the requirements of automobile construction. And if you think that by far the best-selling car at the time was built differently, look at the image below, which

shows the chassis of a Ford Model T.

| At times made up half of the world's motor vehicle stock. |

Incidentally, Henry Ford not only has the credit for bringing this model and its flow production into the world, but also the successful legal fight against the Selden patent. This forced every manufacturer to make absolutely

unjustified additional levies until 1913 and thereby hindered the development of production in the USA. Below is the T-model with a wooden body, albeit a little more elaborated than normal.

| Such a body could also be manufactured in flow production. |

Ford had rationalized to such an extent that, for example, a supplier was given exact dimensions for its wooden transport crate. Their boards could then be used for the floor of the T-model without much processing. Vehicles

with floors made of this material are still manufactured today, albeit in very small series, e.g. certain Morgan models.

From about 1925 there were changes, but the revolution did not materialize yet. Opel was the first German company to start flow production. However, the leader in Europe was Citroën. The cumbersome painting

process came to an end with the introduction of nitro paint. However, this process made higher demands on the quality of the surfaces. It clearly favored processes in which the wooden framework is covered with sheet

metal, such as at Daimler in Sindelfingen.

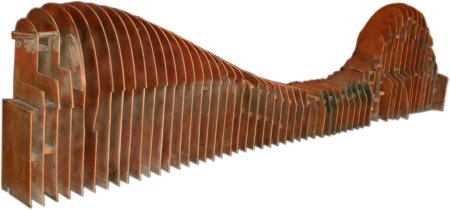

Part of one of the most famous cars of the time, the Bugatti Royale. The wooden frame is prepared for covering with sheet metal. The covering sheets were made by hand, a process now only used for prototypes. Below is a

device to check the work on, here the infinitely long fenders of the Royale.

Below another basis for the processing of sheet metal, this time from the first 50 series of the Porsche 356. It is a very stable construction, not intended for driving, but to ensure that all vehicles are produced with the same

dimensions. By the way, with such procedures, body parts from another car or a spare part, if still available, can by no means be replaced without post-processing.

Finally, the report on a special category, the bodies made of plywood without frames made of pressed steel. This material may be something of a precursor to laminated press materials from plastic, which didn't exist back

then. DKW was a pioneer and mass producer of such light vehicles, which successfully compensated for the thirst and a certain inefficiency of the small two-stroke engines.

After all, there was already Bakelite® with layers of paper pressed together with synthetic resin as a coating. Leather or rather imitation leather was also possible. Already the slightly more powerful types consisted of a

mixture of different materials, including sheet steel for the bonnet.

|