Diesel engine 2 Diesel engine 2

kfz-tech.de/PDM11

What actually characterizes a diesel engine now that gasoline engines have come closer and closer to it in terms of technology? The obvious answer would be that when you open the hood and remove the engine cover,

there is no electric ignition system. So far, so good, but if you try to come into the secret “poison kitchens” of the manufacturers, you may encounter engines that have an ignition system and yet still operate intermittently on

the diesel principle.

This principle emphasizes self-ignition, i.e., injecting fuel with the highest possible resolution directly into the combustion chamber, which is filled with hot air due to high pressure. To be pedantic, you could and should ask

whether the ignition system is strictly switched off when the test subject self-ignites. The answer to this question would then be a clear 'yes and no'. This is the case with the somewhat older concept from Daimler-Benz, but

not with Mazda's SPCCI.

There has been no further mention of the Daimler-Benz concept. With regard to the electrification of vehicles, this is also no longer to be expected. It was interesting because the F700 apparently

managed at times to set all the parameters responsible for combustion, including supercharging, in such a way that controlled self-ignition was possible. In other words, an ignition control system comparable to electric

ignition. Surprisingly, this brought us back to the experiments conducted by Daimler and Maybach in the century before last..

Daimler switches off the ignition in diesel-like operation. If Mazda allows the ignition to continue running, then, according to the manufacturer's explanation, this will initiate a self-ignition.

Accordingly, the electric ignition

serves only to control and prepare to a certain extent a situation favorable for a self-ignition. Unfortunately, this cannot be verified and has not yet been sufficiently verified by independent observers.

So, now we've dealt with the special cases and can finally turn our attention to the standard, which states that self-ignition is a prerequisite for combustion in a diesel engine. High compression plus supercharging

therefore achieves a temperature that ignites injected diesel fuel under all practical circumstances. To illustrate the potential difficulties in safely achieving self-ignition, which Daimler may also have encountered, here is an

experiment:

Dozens of mousetraps are set up in one room. Each one is activated and, when triggered, releases a ping pong ball onto the group. If an additional one is now thrown into the group from the side, in the best case scenario

a chain reaction should occur, helping all the mousetraps to be triggered. In an ideal combustion, no molecule would remain as it was before. In reality, there will be mouse traps somewhere on the edge that were not

reached.

And yet this experiment describes the situation before and during direct injection. This is because the molecules must not only come within a certain proximity to each other. Another decisive factor is their so-called 'energy

level'. What does that mean? Energy from molecules, such as heat, can be recognized by their movement. The hotter it gets, the more they swing. Beyond the limits of the states of matter, they change their distance from

each other once again.

This also means that not only liquid fuel in a higher resolution form is present in the combustion chamber, but also gaseous fuel. The fuel consists almost entirely of carbon and hydrogen, while air consists of almost 80

percent nitrogen and 20 percent oxygen. In most operating conditions, there is twice as much or more of the latter two than would be necessary for the reaction. The main reaction that occurs during combustion is that of

carbon with oxygen, which is why it is also called 'oxidation'.

Incidentally, this is different with gasoline engines. The ratio of air to fuel is pretty much perfect and is even continuously monitored by the lambda control system. Nitrogen also remains, but cannot find any free oxygen

because it prefers to bond with carbon. Based on these basic conditions alone, diesel engines produce more harmful compounds of nitrogen and oxygen, NO2 and NO3.

Now we already have the high temperature and the mixture ratio that is actually favorable for combustion, because there is significantly more oxygen available than in a gasoline engine. Carbon atoms that only find one

oxygen atom (CO) are therefore almost non-existent in diesel engines. But there's still a catch. What if the carbon finds its two oxygen atoms (CO2), but the reaction is not carried out due to many additional air

molecules, meaning that the contents of the combustion chamber are not actually 'ignited'?

kfz-tech.de/PDM12

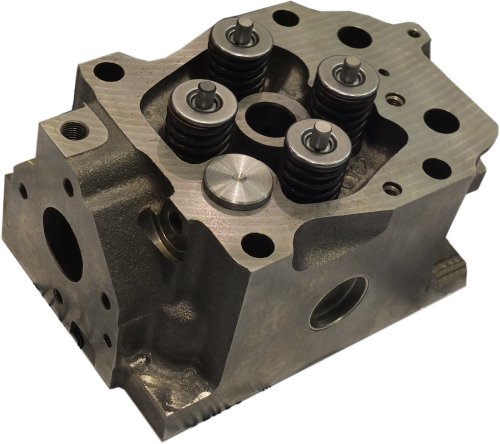

Here is a component that can help with the problem of uneven distribution of fuel and air. It is a single cylinder head. In trucks, these are placed on the cylinders in sequence, regardless of whether they are inline or V

engines. What makes this special is the rotation of the inlet and outlet valves relative to the longitudinal axis, which also makes their operation somewhat more complicated.

The reason for this twist is to generate swirl. The aim is therefore to induce movement in the inflowing gas column, thereby improving subsequent mixing. This is by no means the only way to generate swirl or movement. In

the past, small metal plates were welded onto the inlet valve. There is also the piston, which has to be very close to the cylinder head anyway due to its cavity in order to still ensure high compression.

Although one doesn't speak of squish edges in a diesel engine, but this definitely results in more movement of the air in the combustion chamber. This ensures that carbon and oxygen, the main agents of combustion, and

the individual ignition cores come together. Of course, speed is not insignificant, because only what happens right at the beginning of the work cycle has the best effect on performance, fuel consumption, and perhaps also

exhaust emissions.s

And then it's there, the moment of injection. Now everything has to happen very quickly: mixing, continuous ignition, combustion, and pressure increase. This is the core of what is known as ‘internal mixing’. Injection is of

course particularly important for this. At the edges of the injection cloud, the fuel burns immediately as it leaves the injector. However, only the end-to-end process delivers the desired effects. As with gasoline engines,

there must be no areas of unburned fuel. Carbon that does not burn through produces soot.

Pollutants are produced or they can be deliberately reduced. There is a clearly defined threshold for the treatment of pollutants: the outlet channel. Until then, they are called 'raw emissions'. What has been achieved so far

does not need to be reworked through costly measures. In Euro 6 trucks, the attached components are almost the same size as a car engine.

kfz-tech.de/PDM13

|